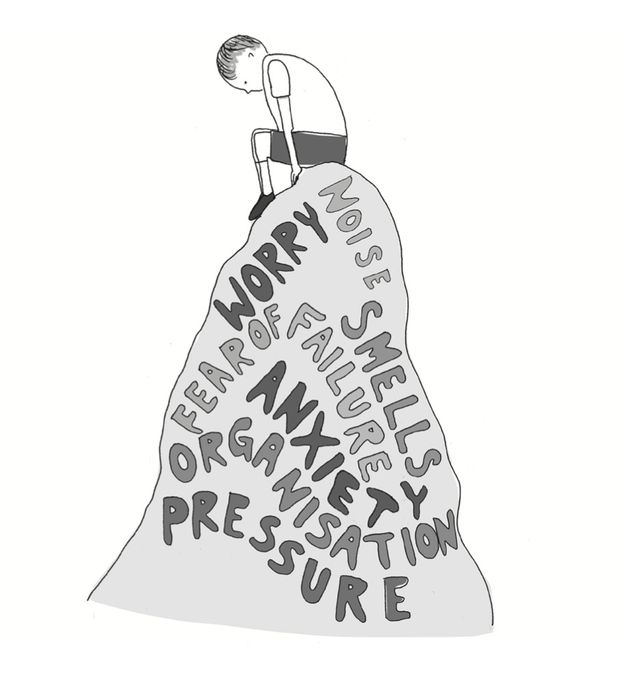

(illustration by Eliza Fricker from my book A Different Way to Learn, published by JKP)

I was talking to a grandmother last week about schooling. ‘I can see the difference’ she said. ‘When my children were young, primary school was relaxed. If the weather was good, they went outside and ran around. If they were sick, they stayed at home. Now with my grandchildren they are seated in desks for more of the day and if they are ill, they are worried that they’ll lose their 100% attendance for the term. The pressure is on to pass their phonics test when they are six and then to learn their times tables at speed by the time they are nine. They feel it and and their parents feel it too’.

There’s lots of talk about SEND (special educational needs and disabilities) at the moment, and how increasing numbers of children are being identified as SEND. It’s less common to ask questions about what SEND really means, and whether the education system creates more children ‘with SEND’ as it becomes more pressured and rigid.

For what SEND really means is that a child cannot learn in the way which mainstream education expects. They cannot keep up with expectations, either for academic work or for behaviour. SEND is something which happens in the interaction between a child and the education system. In a system where no 6-year-old is expected to sit still and learn to write their name, then a 6-year-old who just wants to run around outside isn't a problem. In a system where everyone is meant to be able to read by age 6, then they are.

We know from research that if a child is young in their year, they are more likely to be identified as ‘having SEND’. We know that summer born boys are far more likely to be identified as ‘having SEND’ than autumn born girls. We know that the impact of this immaturity resonates through the years, with the youngest in the year doing less well at GCSE. We know that the number of children ‘with SEND’ is going up year on year.

It's not really plausible that more children each year have difficulties in learning, nor that being born in August makes you more likely to have learning problems than if you are born a few weeks later in September.

It’s far more likely that in the push to ‘drive up standards’ the education system is becomes less, not more, suited to how children develop and learn. It’s more likely that the system is penalising immaturity – and children are inherently immature. That isn’t a lack or a defect, it’s a defining part of childhood.

As the education system becomes more rigid and pressured, we’d expect more children not to be able to manage without adaptations. This is exactly what we see. Those children are holding up the flag for all the others, saying that this system is not child-friendly and doesn’t take account of developmental needs and differences.

What if, instead of having higher expectations of the children, we had higher expectations of the education system? What if those expectations were of flexibility, reducing pressure and prioritising lifelong learning and wellbeing instead of short-term testing?

What if we saw the increasing number of children ‘with SEND’ as a sign that the system isn’t working for the many ways in which children develop, rather than a sign that more and more children have learning difficulties? We’ll never sort the ‘SEND crisis’ until we start looking at SEND as an interaction between children and the education system. The more rigid the system is, the more children it will fail.