Recently a parent got in touch to tell me that her child had stopped going to school, and that after a period of recovery he is doing much better. He started to show interest in life again and wanting to play games. He started asking questions again and his mum was delighted.

Earlier this year, along with millions of others, I was intrigued by a new podcast about autism. was, for a few weeks, Spotify’s top-rating podcast. Everyone was talking about it. The presenter, Ky Dickens, promised to explore the voices of nonspeaking autistic people and the origins of consciousness. The incredible claim was that nonspeaking autistic people could read minds. The story told was that nonspeaking autistic people could meet telepathically with other nonspeakers at a place called ‘The Hill’. The podcast ‘proved’ this through a series of demonstrations where parents were given information not available to the nonspeaking person, who then communicated that information back. The parent might be shown a picture or a number, and the nonspeaking person would say what it was without being shown.

In all my clinical work with neurodivergent people, one question comes up again and again. ‘If it’s my neurology, doesn’t that mean it can’t change?’.

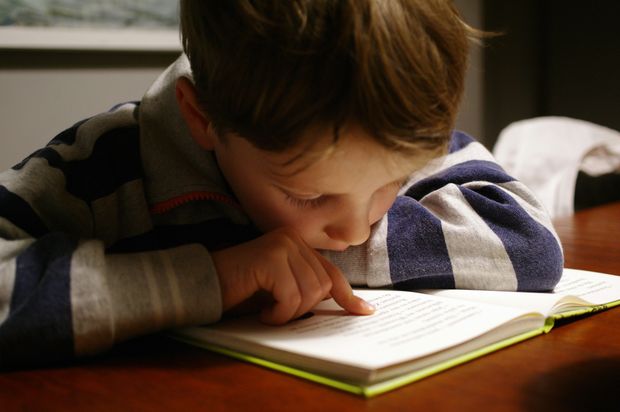

Last year our first self-help book for teens was published, by me and . It’s about burnout, specifically school burnout. It takes a non-pathologising approach to teenagers experiencing burnout - the aim is that they realise they are not alone, and this isn’t going to be forever. It’s full of stories and hope. It is suitable for those with or without a diagnosis - it is neurodiversity-informed but is not limited to those who identify as being autistic or having ADHD. It’s based on psychological principles and informed by lived experience.

Imagine if we treated paper like we do screens. We’d say, oh, you’ve spent an hour reading and 30 minutes drawing – that’s your papertime for today done! Sorry, you can’t write a story until tomorrow, not if you do it on paper. We’d say, no, you can’t learn to do origami, or make a paper model, or write a thank you card to your aunt. You’ve used up your papertime for today. You can do it tomorrow if you’re good. Go and do something else more worthwhile instead.

This week, announced that a new target will be set of 90% of 6-year-olds passing the phonics screening check at the end of Year 1. Currently 83% pass at the end of Year 1 and 89% at the end of Year 2. The government also announced a new reading test for children in Year 8 at age 13.

Things went really wrong for Ollie at school. He would be shaking every evening and grey-faced every morning. He didn’t like the lessons, the noise, being made what to do and the other children bullied him. After years of trying, he stopped going.

No one thinks that they are spreading misinformation. For the most part, misinformation doesn’t spread maliciously. It spreads because people want to share something important they’ve discovered. It spreads because people hear something and it makes sense to them. It spreads because someone has a ‘lightbulb moment’ and they want to let the world know. It spreads because something is a good story or analogy. Misinformation mostly spreads in good faith. Here’s an example. There’s a story I’ve seen repeatedly on social media which goes like this.