We (almost) all go to school, and there we learn many things. We learn that school is a good thing, and that we have to go to school in order to learn. We learn that without school, we’d get nowhere in life.

These beliefs run deep. The things we learn about ourselves and education at school often stay with us for our whole lives.

Then if you have a child who struggles at school, it can be hard to know what to do. Your child is so unhappy, but everyone tells you they seem fine. You’re told they have to be made to go, but at the same time the distress at home is unmanageable. You think that school is essential, but the cost to your child seems out of proportion.

In these courses and webinars about school, Naomi talks about why school can be hard, and why some children are traumatised or burnt out by their time at school. She’ll talk about how parents can help their children to learn and thrive, whether or not they are at school.

Whenever I talk about ways to improve young people’s lives or educate them differently, there’s one question which always comes up. ‘But does it improve their scores in English and Maths?’.

I’m seeing lots of posts bemoaning that this group of Year 11s just don’t seem to care about their upcoming GCSEs. They aren’t motivated or worried about their speaking exams starting in two weeks time and nothing seems to make a difference.

What should we do about attendance? Here’s a pathway I hear way too often. Child manages primary school fine, is happy there and excited to go to secondary school. They start, bright eyed and bushy tailed, and like many eleven-year-olds they find the transition hard. It’s a big step up.

I’ve been observing small children this summer. On beaches, at the swimming pool, in the playground with their parents. Watching their focus and dedication to the things they find meaningful. Watching how much satisfaction they get from doing things their own way, and how strong that drive is. Watching how idiosyncratic their interests are, with one being fascinated by squirrels and another interested in fire engines.

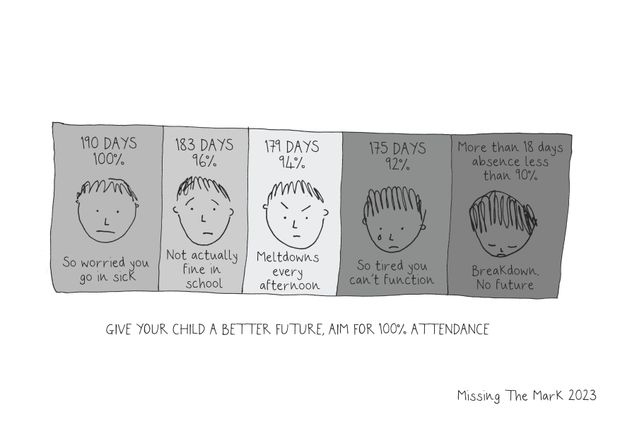

Illustration by Eliza Fricker (www.missingthemark.blog). The rhetoric on school attendance gets ever stronger. Banners are posted around schools, telling young people that every minute missed will damage their chances in life – for ever. Parents are fined and threatened with court and told they are denying their children a good start if they don’t drag them in – literally, in some cases. In their pyjamas. The children’s commissioner says the best place for every child is in school. And yet children do not all thrive at school. School is only one way to learn, and it doesn’t work for everyone. As schooling gets more rigid, with less play and less flexibility, more children suffer. They are the casualties of the system – but they’re treated like the criminals. The outcasts.

1. It is not possible for everyone to succeed in their GCSEs. The exam results are referenced against earlier cohorts, meaning that around 30% will get failing results every year. If everyone does very well one year, they'll shift the pass mark so that some will still fail.

An increasing number of children are struggling to attend school. The conventional approach prioritises a rapid return to their setting. For some children, this simply doesn’t work. They are stuck, not attending school but not learning out of school either. What happens then - and what can we do about it? This illustrated guide lifts the lid on the experiences of children and families who are struggling within the school system and explores how we can work with these young people to maximise their chances of a positive and fulfilled life.

If you are a parent worrying whether self-directed education will work for your child, because you have been told that they have special needs which can only be met in the school system - think again. Neurodivergent children experience and interact with the world differently to many of their peers. Standard educational systems often fail to adapt to their unique strengths and ways of learning. School, and even the act of learning, can become a source of great anxiety and trauma. Self-directed education offers an alternative to traditional schools that can help neurodivergent children develop at their own pace and thrive.

Children are born full of curiosity, eager to participate in the world. They learn as they live, with enthusiasm and joy. Then we send them to school. We stop them from playing and actively exploring their interests, telling them it's more important to sit still and listen. The result is that for many children, their motivation to learn drops dramatically. The joy of the early years is replaced with apathy and anxiety.