Recently I’ve been making people angry online. Very angry. In fact just in the last couple of days I’ve been told that I’m harmful, ableist and ignorant. The message is clear from some people. Stop it.

Last week my Facebook page was hacked. In a few moments I was kicked off my page altogether, the verification details were changed and I wasn’t sure if I’d be able to get it back at all.

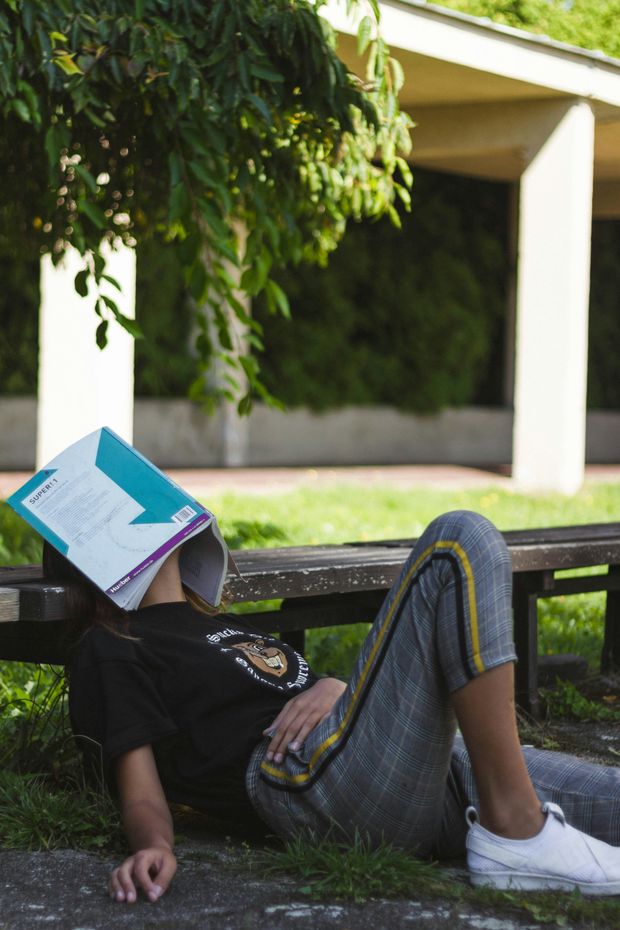

When I was young, I got very good at taking exams. I sat nine GCSE’s, each with at least two papers. I went to 6th form college and sat more exams there. Onto university, and at the end of each year there were more exams which I had to pass in order to continue. Summer after summer, dominated by high stakes exams. I sat in hot exam halls with my clear pencil case and wrote until my hand hurt.

When I was a teenager, I dislike the school I was at. I mean, really disliked it. So much so that it made me feel ill. I felt like I was walking through a hostile environment, a target on my back. I felt both anonymous and far too visible at the same time. The last thing I could do, as I trudged from class to class, was learn anything.

I wish I felt good about the ‘ ’ definition of school readiness. It’s a list of 29 ‘skills’ which children need in order to be ready for school. It includes practical self-care like putting on and off their coat, things which make it easier for schools to manage children like ‘following simple instructions’ and descriptions of the sorts of things that many children this age do naturally, like ‘exploring the world around them’. But it makes me uncomfortable, and that’s because of how it’s been framed. It’s not being talked about as a description of a stage of children’s development – an indicator they might be ready for formal schooling – it’s being talked about as something which parents should be ensuring their children reach. Skills they should be ‘practicing’ to make sure they get the best possible start. In other words, it’s going to be used as another way to blame parents when schools are not ready for their children.

When we make children do something, their relationship with it changes. We know that, because most of us have the same experience as adults.

I talked to a parent recently whose daughter had had a difficult start at school. She’d been fine at nursery, but when school started, the expectations changed. There was more sitting still and listening and maths and phonics.

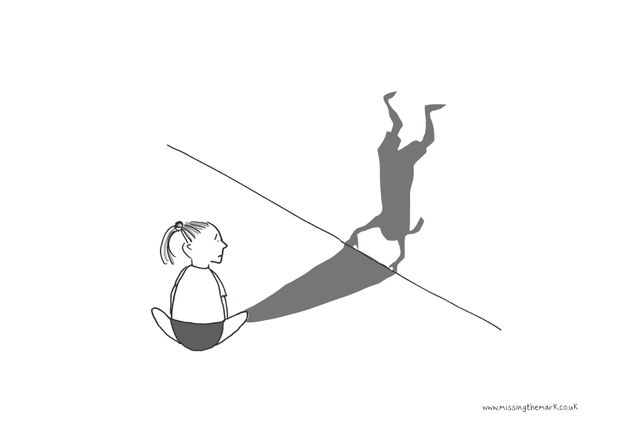

Coping. Resilient. Managing. Why do these words put so many parents on edge? It’s because they can be so easily used to dismiss children’s distress. The distress which perhaps only parents see. The explosions after school, or the kicking and screaming in the mornings. The worrying all day on Sunday, about the week to come. The weepiness, or the anger bubbling under the surface, always just about to show itself. The way that they are walking on eggshells. ‘They’re fine once they’re here’, parents are told, and they feel that they can’t keep saying ‘Well they’re not coping at home’ because they will be told that perhaps that’s because they need to introduce a sticker chart, or more structure, or a visual timetable. Perhaps they need firmer boundaries or harsher consequences.