Illustration by @_missingthemark

When a child has difficulties at school, it’s common to locate the problem in the child or their family rather than in the school. Here’s what families tell me about that.

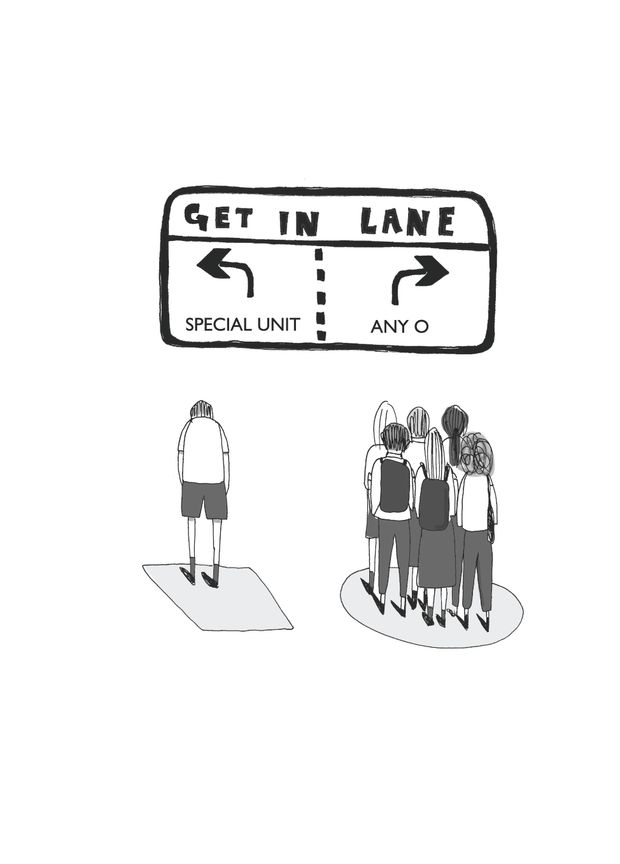

Children who don't fit the mould are told that they need to try harder, make less fuss, be less different. The way that everyone else fits in is held up as what to aspire to - no matter if the child thinks otherwise.

Special arrangements are sometimes made. They come out of class for extra reading, or they stay seated in the hallway when everyone else is in class. They might have a special card they can raise in class if they're overwhelmed. They come in late or leave early.

Adults think of these things as support but for some children it feels quite different. They feel 'other', and not in a good way. Everyone else does it one way, and they are the stand-out, the exception. The other kids notice and they're often not kind.

Children tell me that they think it's their fault. They don't know why they can't be like everyone else, they just can't. They tell me that they are stupid, or even bad. They tell me they hate being marked out. This often includes their diagnoses. They are assessed and evaluated, and it’s usually for adult purposes and goals. They may not have been asked at all.

Sometimes they grow to hate the words which are used to define them, blaming the words for the way that they feel. Sometimes the words are used to bully them - many adults have told me that the word 'special' sends a shiver down their spine. They don’t want to be associated with the ways they have been described and categorised.

Their parents are often reframing differences in a positive way. They may have their own diagnoses which they have found life-affirming and liberating. For them, a diagnosis has enabled them to find their people and be themselves. They tell their children it's fine to be who they are.

But for the children, it all seems like hot air. It's not liberating when you find school so anxiety-provoking that you can't go. It's not life-affirming when no one will play with you. Why should you be positive about difference when you'd like to be just one of the gang?

What’s the point in being yourself if that means you have no friends? It’s not true for all that if you’re just yourself, others will like you.

I've worked with dyslexic adults who cry when they tell me of the shame they felt aged seven, when everyone else could read. I've worked with autistic adults who are still upset when they remember being the last one standing, unchosen for P.E because they had no friends. I remember myself, different at secondary school in so many ways. I didn't want to (and couldn't) be like everyone else, but I was bullied and ostracised for who I was. Adults tried to tell me I was fine as I was, but it was obvious the other teenagers didn't think so. My environment told me that I was wrong, and that was much more powerful than the words.

It's important for parents to be positive about difference, but it's not enough. We can't expect our children to appreciate themselves when their way of being means that they are ostracised. We can't tell them it's okay to learn at their own pace when it so clearly isn't.

We're up against a system which isn't flexible enough. We're up against a set of standards which tell our children that they are failing. We're up against a system which prioritises conformity and compliance, with kids who can't or don't want to conform.

We need a system which starts with an assumption of difference and variation. Where the aim is for each child to end their education knowing that they are ok, just as they are. No matter if they struggle to attend full-time, or if they learn to read when they are 6, 8 or 12.

For that is what our children carry through life with them. They won't remember their GCSE history syllabus in 20 years, but they'll remember how it felt to be laughed at, to be excluded, to be told not to be so silly when they explain how the playground makes them scared. They’ll remember the looks and giggles when they are taken out of class for extra reading or when they sit through playtime doing the maths which they just can’t understand.

Enough about how things aren’t working. Let’s think about change. What would a system look like if the priority was for each and every young person to end school feeling good about themselves, no matter what their differences?

It's hard to imagine because it's so far from what we have now. It would mean questioning deeply held convictions at the heart of the school system, and putting flexibility ahead of standardisation. It would have to accommodate variable outcomes as well as different pathways. It would have to start with the assumption that each person develops differently, and that the norm fits very few.

Then, we might finally have a system which was fit for all. And that is what inclusivity really means.