Click on a button to jump to our webinars, courses, books or blog posts on Anxiety

We all feel anxious sometimes. We worry about whether we will get all our work done, or whether we might get a speeding ticket for going past that camera at 36 mph. We worry about what will happen to our children when they grow up. Anxiety is a part of human existence. We need it, it urges us to think carefully and not to rush into things.

Sometimes, however, anxiety goes beyond what is helpful. It can become a constant hum in our heads. We can feel unable to sit down or to concentrate, because we are so wound up. We can become highly distressed, because the feelings are so unpleasant and relentless.

When this happens to a child or teenager, it can affect the whole family. They often want to avoid their anxiety because it feels horrible, and then that can become a trap. Avoiding our feelings means they get more intense, and so the world gets smaller and smaller.

In my webinars and courses, I explain anxiety and how it works. I’ll outline some ways in which families can manage anxiety, so that their children can grow and thrive.

How can parents help when their children are so distressed that everything seems too much?

This mini-course for teenagers to watch by themselves is about what anxiety is like for teenagers, and how sometimes the things we do to try and make anxiety better, end up making it worse. It has some clips from Jenna, who is 18 and who has lots of experience of anxiety. She’ll tell you about what helped her and how she’s manages to live the life that she wants to live.

Many teenagers are anxious, and their parents don't know how to help. Worries about school, worries about friends, anxiety which just seems overwhelming - what's going on? Naomi will explain how anxiety works and how brains change in adolescence. She'll go on to explain why adolescents are often anxious - and give parents some ideas as to how to help their teen.

Many autistic children are anxious. Dr Naomi Fisher, clinical psychologist, will help you understand some of the reasons and will show you some ways you might be able to support your child. You will leave with a better understanding of what might be going on, and some ideas as to how you as the parent can help.

Why are so many autistic teenagers anxious - and what can parents do to help? Gain understanding, insight and practical tips in this mini-course by Dr Naomi Fisher.

In this practical and engaging course, Dr Naomi Fisher, clinical psychologist, will help you understand the developmental changes of early childhood. She'll show you how anxiety works, and how parents can make a difference. You'll understand your child better, and therefore be better able to help.

In this course, Dr Naomi Fisher will explain the developmental changes going on between the ages of 6 and 13. She'll explain how anxiety works, how children can get stuck, and what parents can do to help. This course is suitable for all children who experience anxiety, whether they have a diagnosis or not.

Some children and young people seem to withdraw from life. Their anxiety becomes so severe that anything which might have helped seemed to make things worse. They may find it hard to come out of the bedrooms or to leave the house. Parents are left not knowing what to do next. Naomi will help you to think about severe anxiety through the lens of the nervous system and give you some practical ideas to help your child.

Many children with learning disabilities are anxious - but those around them might not recognise this as anxiety. They're unlikely to say 'I'm worried' but instead will show us their feelings through their behaviour. Behaviour which can be hard to manage. Naomi explains how anxiety works and give you practical ideas to reduce anxiety and help your children thrive. It is suitable for parents of children with learning disabilities or global developmental delay.

Life is full of transitions - and many autistic children find them really difficult - which means that their parents find them hard too. Life can feel like walking on eggshells. Dr. Naomi Fisher will help you gain a new understanding of why transitions are so hard, what makes it worse - and how to help.

Dr Naomi Fisher will explain OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder) and how it can interact with autism. She'll describe how parents and children can fall into OCD traps, and what to do to get out. She'll give you some ideas to help your child, even if they themselves don't think that there's a problem.

EOTAS is a provision for students whose needs cannot be met within a traditional school setting, and is a bespoke, individualised education. In this course, Dr Abigail Fisher, educational psychologist, will help you understand the process, benefits, potential costs and unexpected challenges of EOTAS.

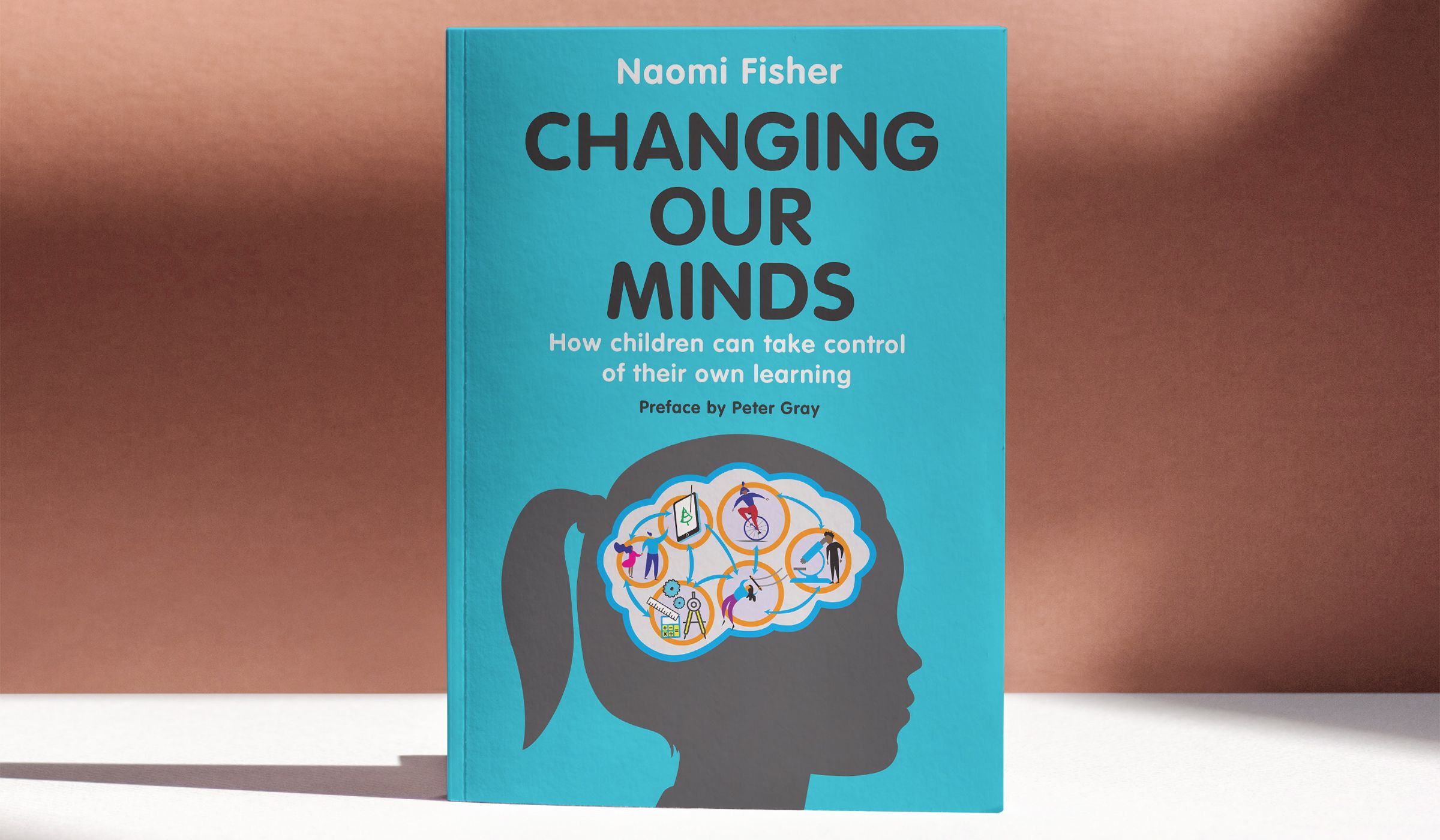

Children are born full of curiosity, eager to participate in the world. They learn as they live, with enthusiasm and joy. Then we send them to school. We stop them from playing and actively exploring their interests, telling them it's more important to sit still and listen. The result is that for many children, their motivation to learn drops dramatically. The joy of the early years is replaced with apathy and anxiety.

Last week a parent was telling me about their highly anxious child who isn’t going to school. They had gone to see a counsellor, and after hours of coaxing and preparation they got to the room. The first question (after names and introductions)? ‘So how can we get you back to school?’.

No one thinks they will have a child who doesn’t want to open their presents - and who even when the paper is off, doesn’t open the boxes. No one thinks that they’ll be looking at last years’ gifts still sitting in a pile in the cupboard, as next Christmas is fast approaching.